The alpaca (Vicugna pacos) is a close relative of the fellow South American llama (same family, Camelidae, literally ‘the camel family in Latin’). The alpaca is much smaller than the llama, coming in at a bit over 100 pounds and under four feet tall at adulthood, whereas a llama may weigh as much as 400 pounds and be well over 700 feet tall.

Depending on your place of residence, perhaps you’ve seen ads late at night that extoll the glories of alpaca farming. According to these ads, the ‘alpaca lifestyle’ is an easy and extremely profitable one that beats the alpaca-fiber-pants off the suckers who actually work for a living. However, like most investment opportunities involving hoofed South American animals, raising alpacas may not be the cash machine that creepy on-camera testimonials claim it is. A quick internet search of the term ‘alpaca scam’ reveals all manner of aspersion cast upon the American alpaca industrial complex, from the obvious (there’s really not much of a market for alpaca wool in the US) to the conspiratorial (that it’s all a massive pyramid scheme that eventually has to collapse).

Might not be for you…if you like working for a living. Loser.

Animal Review does not take an official position on the ‘alpaca lifestyle’ and holds no positions in any alpaca stocks.

If you’re not a watcher of early-morning TV and like most people have no idea what all this is about, alpacas and human beings have coexisted for centuries. In South America (where they’re well-suited to a frigid, high-altitude lifestyle in the Andes Mountains), alpacas have been used as beasts of burden, for meat, and, most notably, for their fine fiber, which is considered much finer than llama fiber by people who pay attention to this kind of thing.

Phenotypically, an alpaca looks like a weird sheep/horse/goat mix, and indeed many leading researchers believe that this is precisely whence they originated well over 20,000 years ago, somewhere on the Eurasian steppes. Following a horrifying series of mating errors between sheep, a horse, and some goats, the newly-minted alpaca hopped a land bridge to South America, where it was immediately beloved for its agreeably stupid disposition, which, again, squares well with the notion that they are the products of interspecies breeding that should never have occurred.

Weirded out yet?

Long story short, alpacas became big in the Incan Empire, where wealth was in part demonstrated by the number of alpacas one owned. And here’s where the dumb alpaca has a lot to answer for: only fourteen large animals have been ever been successfully domesticated: sheep, goats, cows, pigs, horses, Arabian camels, Bactrian camels, llamas and alpacas, donkeys, reindeers, water buffalos, yaks, Bali cattle, and Mithans (a type of ox).*

Of these, llamas and alpacas are the only New World domesticates.**

So flash-forward to 1532, when Spanish Conquistador Francisco Pizarro and 168 of his men show up with horses in what is now Peru. And in about one day, the Spanish and their horses defeated thousands of Incan fighters in open battle, captured the Incan god-king Athualpa, and generally made Spain look awesome.

Their stunning victory was in large part due to the Spanish caballeros, who rode into battle astride their massive steeds, terrifying the Incans, who of course had never before seen horses. So frightening were the warhorses that even the Conquistadors themselves were scared of what they had gotten themselves into. Recalled one of Pizarro’s men: ‘We really whipped our horses into a frenzy, and quite honestly, I was worried Old Kicky would freak out and throw me off him. But he was pretty cool about it.’

Anyway, while the Spanish horses were conquering an empire, the Incans’ alpacas were standing around looking for some more grass to eat.

Thanks.

Between the generally creepy appearance, suspect breeding, alleged pyramid schemes, and allowing an ancient empire to be defeated in an afternoon, alpacas have a lot to answer for.

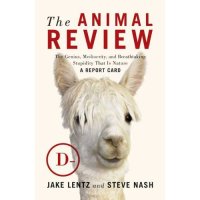

GRADE: F

*c.f. Jared Diamon’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, which you can also rent in DVD form from Netflix and pretty much get the jist of.

**This does not include dogs, which is probably good, since let’s not lump in dogs with alpacas.